Rakitata River

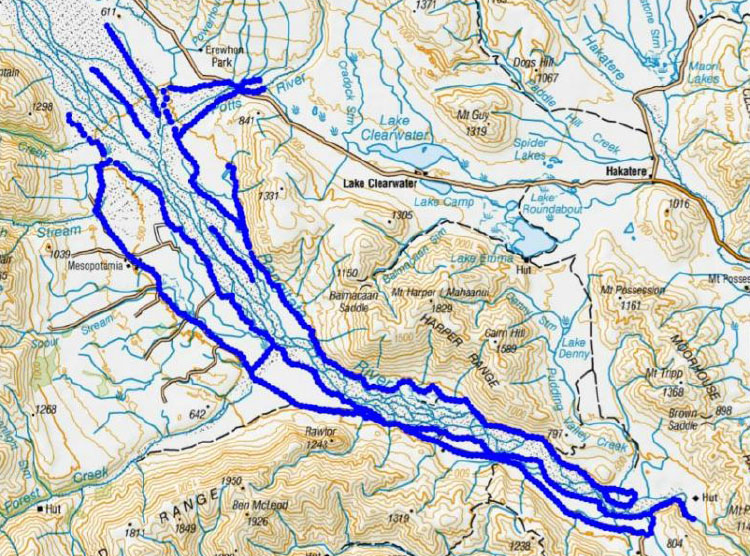

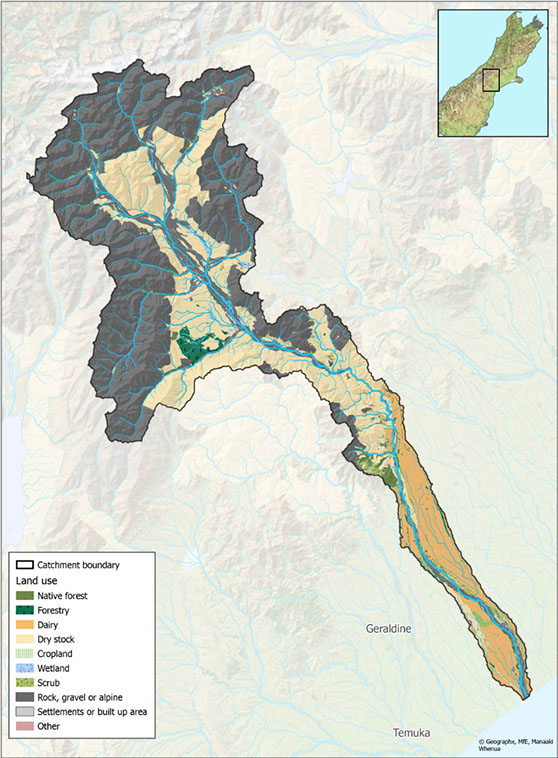

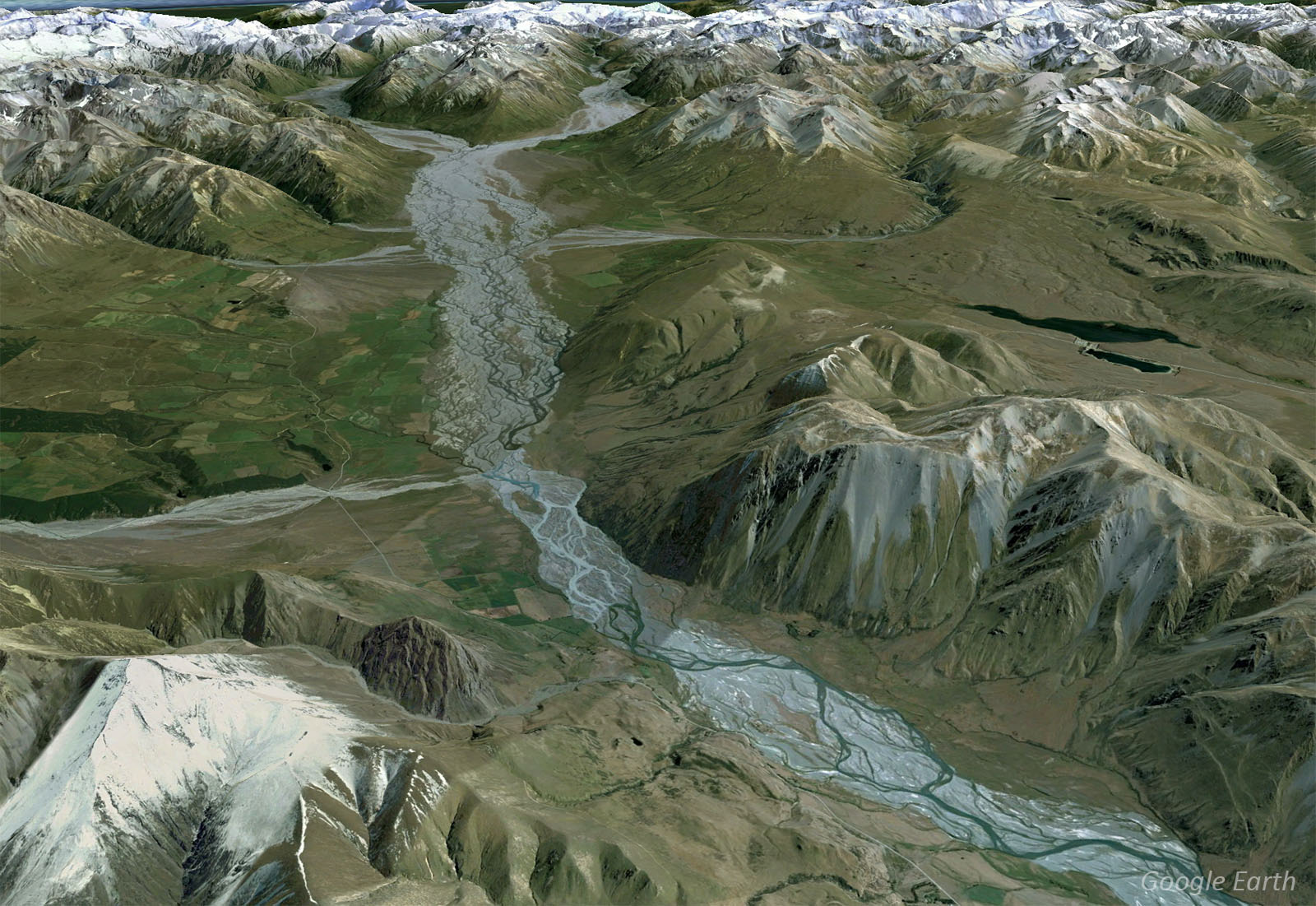

The Māori name Rakitata (Rangitata) has been variously translated as ‘day of lowering clouds’, ‘stairway to heaven’, and ‘the side of the sky’. With a catchment area (click for interactive map) of 1,773 km2, the Rakitata River begins its journey from the Southern Alps at the confluence of the Clyde and Havelock Rivers, a region made famous for its location of Edoras and Helm’s Deep in Lord of the Rings.

Before the Rakitata River enters the Canterbury Plains, part of it is diverted to the Rakitata Diversion Race (RDR) for irrigation and hydroelectric generation. Built between 1937 and 1944, the RDR supplies water to the Montalto and Highbank schemes before joining the Rakaia River. The Rakitata River passes through the Rangitata Gorge in the Alpine foothills, and flows southeast for 121km before entering Canterbury Bight 64km northeast of Timaru.

Towards its mouth, the river splits into two streams, forming the large (17km x 5km) lens-shaped delta island, Rakitata Island.

Biodiversity & cultural significance

The Rakitata River is the border between two zone committees with two different Zone Implementation Programmes (ZIPs): Ashburton and Orari-Opihi.

Download the October 2019 report for DOC: Rakitata Catchment Values

Extract from the Ashburton Zone Implementation Program: ‘Water is precious and limited. It must be managed in ways that recognise and balance its importance for cultural, economic and recreational use, aesthetic and landscape values and biodiversity values – and delivers both individual and community good. We affirm and recognise tangata whenua and the value they place on mahinga kai, and the priority of available high quality sources of drinking water in rivers, waterways and aquifers. We also recognise the intrinsic value of aquatic ecosystems and river health (quality and flow), and the need to both prevent further decline and then restore wetlands and waterways. We know that to achieve all the targets of the CWMS within our zone it is necessary to strategically manage the water within our zone and provide opportunities to bring more water into the zone.’

Extract from the Orari-Opihi Zone Implementation Programme (ZIP): ‘The upper reaches of the Rakaia and Rangitātā represent relatively weed free glacier fed catchments in almost pristine condition. Throughout their catchments, these rivers have outstanding fishery and habitat values… The Rangitātā…provides outstanding habitat for many rare birds, fish, plants and other species, as well as a wide range of recreational values.’

Important Bird Areas on the Rangitata River: links to 6-page PDF file that includes maps, habitat types, and threats relevant to this river. This document was extracted from Forest & Bird’s 177-page 20Mb file on all rivers, lakes, and coastal areas.

Hakatere Conservation Park straddles sections of the upper Rakaia and Rakitata Rivers, is part of one of the best wetlands in the country. A national wetland restoration project was started in 1997 and involves three premier sites: Whangamarino in Waikato, Awarua/Waituna in Southland and Ō Tū Wharekai here in Canterbury. The rivers, lakes, tarns and swamps of Ō Tū Wharekai have their own special range of species; some of which are rare, for example our kettle holes are home to 23 threatened plants. Although each wetland habitat is unique, all waterways are interconnected, breathing life into the Hakatere basin.

Conservation activities

The Rakitata River is one of ECan’s flagship biodiversity programmes and one of 14 priority catchments in the Department of Conservation’s Ngā Awa river restoration programme. The goal of the restoration is to imprint the whakapapa (geneology) back onto the river and restore its mauri (life force). Mauri represents the essence that binds the physical and spiritual elements of all things together and generates and upholds all life. It is an essential element of the spiritual relationship that Arowhenua have with the Rakitata River.

The Implementation Strategy for the Braided River Flagship Programme – Upper Rakaia and Rangitata Rivers (2011), outlines the initiatives for both rivers.

- 2023: Monitoring of nesting braided river birds in the lower reaches of the Rangitata river during the 2022-2023 breeding season

- 2022: Increasing wader abundance: vital rates of tōrea and residual pest indexing. Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research

- 2022: Monitoring of braided river birds in the lower reaches of the Lower Rangitata river during the 2021-2022 breeding season (Wildllands)

- 2021: Review of 6-year upper Rangitata River predator control project – Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research report for ECan

- 2020: Wild Animal Management Plan, Upper Rangitata River Catchment Report prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited for the Upper Rangitata Gorge Landcare Group and Environment Canterbury.

- 2020: Upper Rangitata Trapping Report (DOC)

- 2019: Upper Rangitata River 10 Year Weed Action Plan (16Mb Boffa Miskell)

- 2019: Rangitata River Catchment Conservation Values

- 2019: Major study of Rangitata River (Timaru Herald article)

- 2019: Presentation at the Braided Rivers Seminar on details and current outcomes of the project

- 2017: DOC Newsletter including updates of work and outcomes

- 2016/17: DOC report on wrybill and black-fronted tern nesting success

- 2016: DOC Upper Rangitata predator control programme and results

- 2016: Site assessment for the possible reintroduction of kaki/black stilt (BRaid workshop)

Water flow & floods

Images sourced from the CanterburyMaps and partners and licensed for reuse under the CC BY 4.0 (link is external) licence.

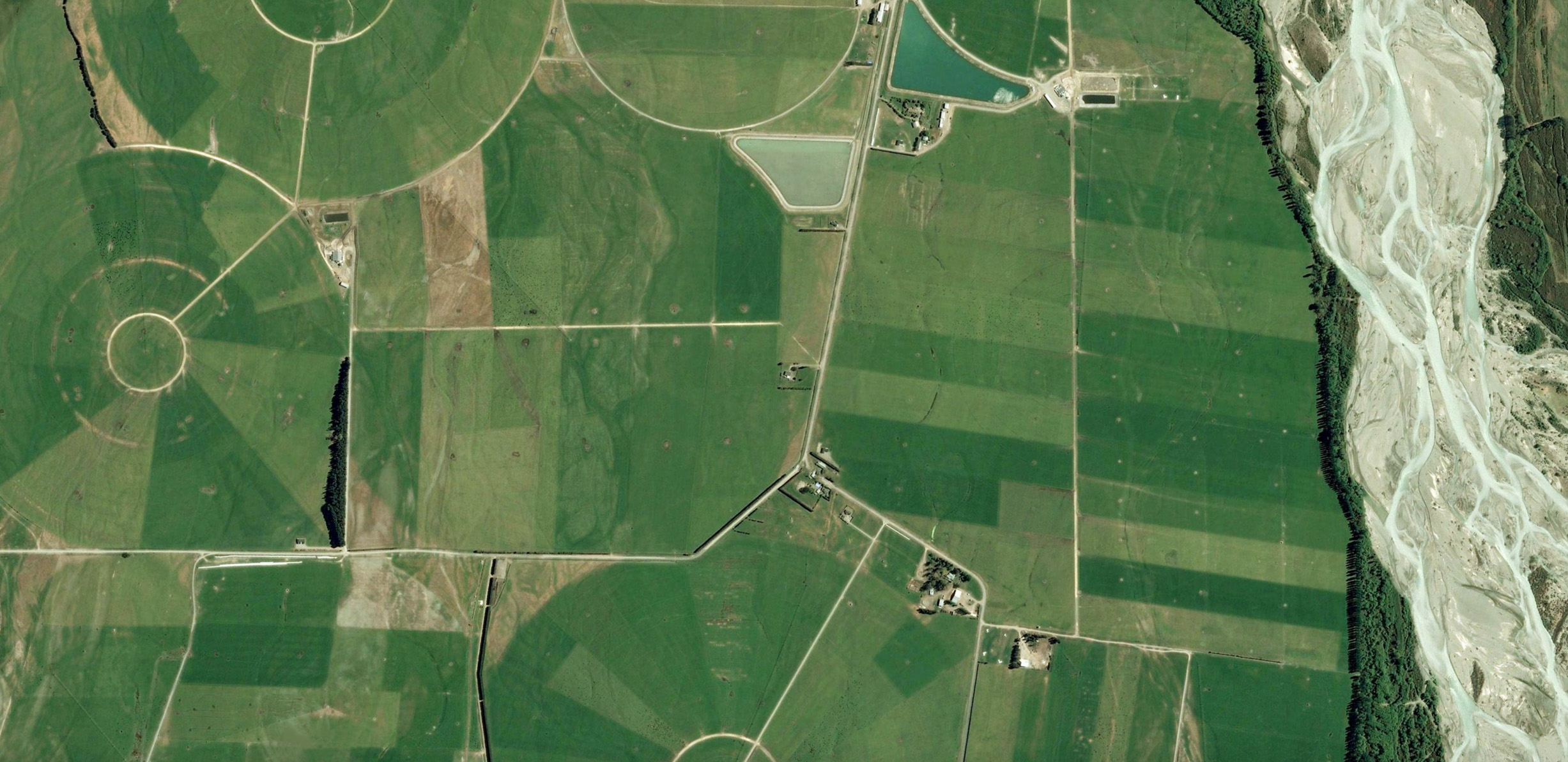

“From the ground, it would have seemed like chaos; floods of water rampaging over the plains, damaging anything in its path. But from above, a different picture was emerging. Environment Canterbury (ECan) staff were photographing the floods from the air, later stitching together the images to create a mosaic of the event.

“It showed the floodwaters were following a predetermined pattern. The flood was itself a river, with twists and braids and tributaries, much like the Rangitata itself.

“A zombie river, long ago buried beneath asphalt and housing and irrigators, had been revived.” – The Rewilding Project / Stuff

The December 2019 flood peaked at 2270 cumecs, with a catchment rainfall of 875mm extending over seven days. As the flood was well beyond the design capacity of infrastructure, the outcome was, unexpectedly, considerable and very costly.

This highlights a key problem that river manager are now facing. NIWA has forecast more frequent and larger floods as the climate changes. All the research points to rivers needing to be given more ‘room to move’ to accommodate these future floods. And yet the High Court has ruled that the legal width of a braided river is significantly less than previously defined.

- River Report 24-hour Infoline: river flows (updated twice daily), rainfall, sign up for text alerts

- Catchment map and monitored sites include scientific indicators for water quality (LAWA: Rangitata River)

References & research material

- 2021: The Rewilding Project / Stuff

- 2019: DOC; Rakitata River Catchment Values

- ECan document library: enter ‘Rakitata or Rangitata River’ in the ‘keywords‘ search field

- DOC catalogue of scientific publications: enter the relevant search terms in the ‘search’ dialogue box. You may need to vary your search, for example ‘black stilt’ gives far more results than ‘kaki’ or ‘kakī’

- See Rivers for a more comprehesive list of braided rivers research and reference material