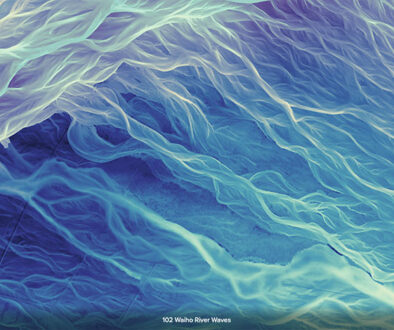

Protecting wrybill in the upper Rangitata

From Department of Conservation Ranger, Murray Thomas

Protecting an unusual endemic bird, the wrybill, and the endangered black-fronted tern is the primary aim of a predator trapping programme on the upper Rangitata River.

Results from the last two seasons show the expected wrybill predation rate of between 10-25% of all nests was reduced to zero, says Geraldine/Raukapuka ranger Brad Edwards.

The wrybill/ngutu pare is one of only two birds in the world with a beak bent sideways (to catch insects under stones) and is classified as nationally vulnerable.

There are only about 5,000 left, which gives it the same status as the spotted kiwi/roroa.

“Wrybills can live up to 22 years. Each one is precious because their numbers are low despite the number of breeding seasons during a lifetime,” says Brad.

He calls them, “Cool little birds,” with cute bumblebee-like chicks that take 30 days to fledge.

Their plumage perfectly matches the greywacke stones, and their natural instinct when threatened is to freeze. While that worked against their natural winged predators, it makes them sitting targets for introduced mammals.

Like the wrybill, the black-fronted tern/tarapirohe breeds only on the braided rivers of the South Island. Its numbers are now estimated to be from 5,000 to 10,000.

Also being protected by the Rangitata project are the South Island pied oyster catcher/tōrea, the black-billed gull/tarāpuka, and the pied stilt/poaka.

Prior to the trapping programme, the average number of surviving wrybill chicks per breeding pair per season was 0.47, but during the last two trapping seasons, that number had lifted to 0.75, Ben says. And a 0.75 average is what is needed for success.

The trapping programme, aided by Environment Canterbury and Land Information New Zealand, has also ensured a significant difference in the rate of surviving black-fronted tern chicks on the upper Rangitata compared to the lower reaches where no trapping is done.

Last year 36% of nests hatched, and 11% of chicks fledged successfully, with 11% of nests predated. While that sounds low, outside the trapping area 82% of nests were predated and no eggs hatched. Nothing fledged.

Predation is just one threat these birds face. The nests are vulnerable to flooding and weeds encroach on suitable sites.

“Predation is the thing we can really change, and get good results.”

The upper Rangitata is part of the Ō Tū Wharekai wetlands being fostered by DOC within the Hakatere Conservation Park.

Geraldine biodiversity ranger Damien Bromwich is in charge of the trapping programme. He says the trapping line stretches 125km, equal in distance to that between the edge of Christchurch and Geraldine.

Over the last two seasons, the traps have caught 166 stoats, 139 ferrets, 60 weasels, 334 rats, 119 possums, 197 cats, 47 mice, 154 rabbits and 1,754 hedgehogs. Hedgehogs may not look like killers but they eat eggs.

The operation runs from July to February and covers 12,000 hectares of the river bed and adjacent land. Traps are checked monthly and numbers recorded on an app, Damien says.

Although new pests fill the void after trapping stops, the nesting area is protected throughout the breeding season until the birds have fledged.

Most of the trapping is on the riverbed but some is on surrounding farmland, and Damien says farmers’ co-operation has been integral to the programme’s success.