Invertebrates

In spite of their size, invertebrates are arguably the most important but least understood animals in braided river ecosystems.

“The truth is that we need invertebrates but they don’t need us. If human beings were to disappear tomorrow, the world would go on with little change. But if invertebrates were to disappear, I doubt that the human species could live more than a few months.” – Biologist E. O. Wilson

The complex and wide-ranging habitats in braided river ecosystems are home to millions of tiny and incredibly diverse invertebrates that include insects, spiders, crustaceans such as freshwater crayfish koura, molluscs such as snails, mussels, worms, and leeches. They range in size from less than 1mm long to over 10cm long, and live in the diverse and dynamic aquatic and terrestrial environments that make up the braidplain. Even the largest of them can be hard to see at first glance because, like some braided river bird species, they’re incredibly well-camouflaged.

Aquatic invertebrates

See the NIWA website for a guide to aquatic invertebrates.

River birds feed on invertebrates, primarily insects and some worms, found in braided rivers. In the water, under the stones, are the larvae of insects such as mayflies and caddisflies, particularly in riffles where the bubbling water has a high level of oxygen to support large insect numbers. Mayfly larvae are fast-moving and hide under rocks.

Some caddisfly larvae build a case of sand grains to hide in. Adult flies fly over the water. In a braided river, the availability of food is always unpredictable. During lean times, the birds must range from the riverbed into stable side channels and pond areas to find food. Others will use the opportunity of ploughed fields to search for beetles and worms.

Each bird species has evolved to feed on insects in distinct ways. Specialisation minimises competition for food between them.

The long bill of pied oystercatchers tōrea allows them to probe deep into mud, sand or under pebbles, to find worms and insects. As well as using riverbeds, oystercatchers also probe for worms and small beetles on pasture and ploughed land. On coastal areas, they feed on shellfish (hence their name) small crustaceans and cnidarians (jellyfish).

Black-fronted tern tarapirohe and black-billed gull tarāpuka feed on the wing over main channels, catching insects in the air or scooping insects and fish from the water’s surface. They sometimes feed on insects from surrounding farmland.

Black stilt kakī, with their long legs, wade in deeper slow-moving water, reaching insects on the bottom with their long necks and bills. Sometimes they dart at insects and small fish in riffles or muddy areas.

Wrybill ngutupare feed in shallow channels, riffles and the edges of pools. Their bent bill is specially adapted to allow them to reach under stones for mayfly larvae.

Banded dotterels pohowera feed on moths, flies and beetles found among scattered low vegetation on the high parts of the riverbed and along the muddy edges of lakes and rivers. They have a distinctive run-stop-peck-run movement while they feed.

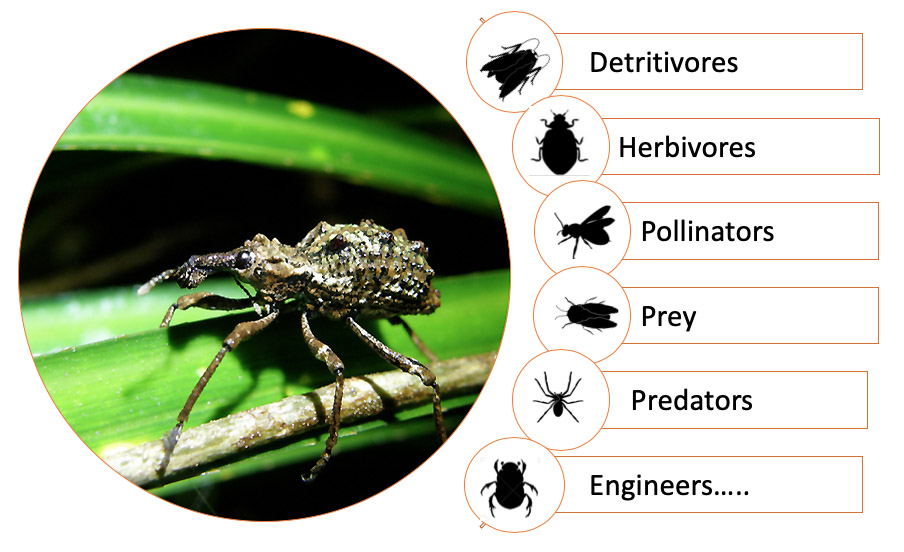

Terrestrial invertebrates: fundamental ecological values

Some terrestrial invertebrates such as flies and mosquitoes start out life as aquatic invertebrates. Others live their entire life cycle on land. While some of these purely terrestrial species most likely are food sources for braided river birds, exactly what their roles are in braided river ecosystems is largely unknown. Some moths or butterflies, for example, may—or may not—be important pollinators for some braided river plants.

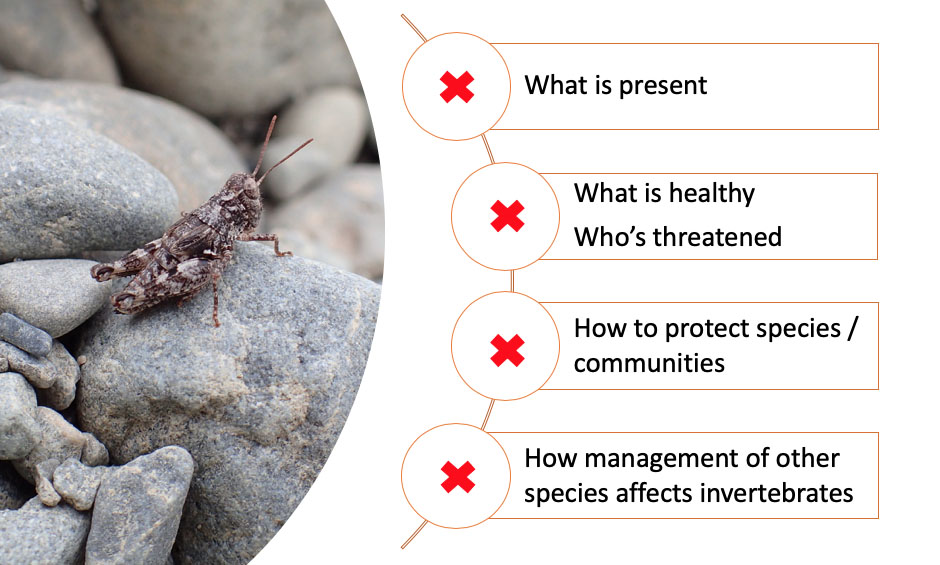

The list of what’s not known about their multitude of roles is far larger than what is known. However, based on what we know of other ecosystems elsewhere, invertebrates perform vital ecosystem services that humans and other organisms depend upon not just for our well-being but for our survival.

We do know that at the rate we’re losing braided river ecosystems to weeds, agricultural conversion, and other threats, many species may go extinct before we understand their importance.

What we know about terrestrial invertebrates in braided rivers

Extract from DOC Management and Research Priorities (2019): “Despite the high numbers of invertebrate species, and the likelihood of a high degree of endemism within these species, Canterbury braided river invertebrate biodiversity is poorly understood. Species most likely to be specific to braided rivers are the less mobile species, such as flightless species and herbivores that have close associations with host plants (e.g. Muehlenbeckia and associated moths, Roulia etc.), and species adapted to specific substrate properties such as the Tekapo ground wētā. These, along with some of the smaller invertebrate species, are less able to respond to pressures, and therefore most at risk from ecosystem-level threats such as host plant decline via competition, weed invasion, and changes in hydrology and vegetation resulting from climate change (e.g. rainfall gradients, reduced numbers of frost days etc.).”

- 2024: Invertebrate communities of the Cass, Ashley, and Aparima Rivers and methods for monitoring impacts of management and environmental change (PDF)

- 2024: Braided Rivers seminar presentation; Land-based invertebrate monitoring on Canterbury braided rivers (PDF)

- 2022: Braided Rivers seminar presentation; Invertebrate biodiversity of the Ashley-Rakahuri and Cass Rivers: impacts of weeds and flooding (PDF, also see the video recording of this presentation)

- 2021: Interim report on research work being carried out on braided rivers

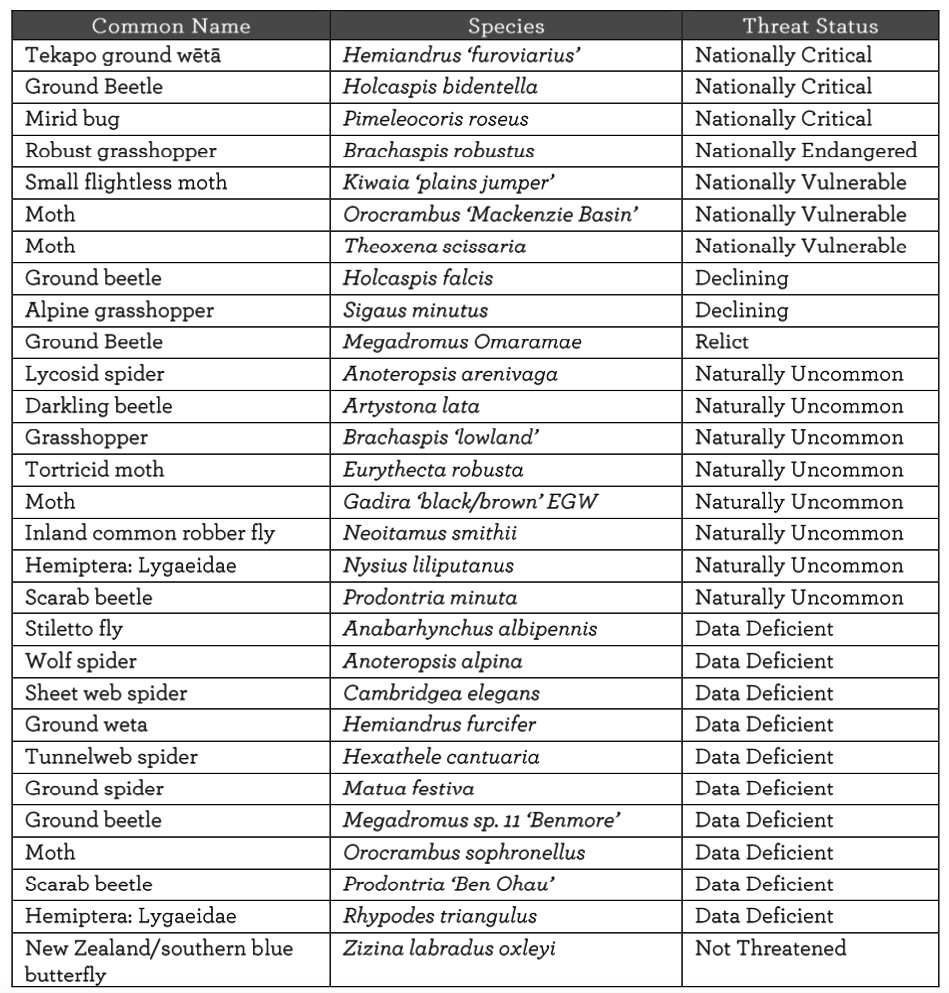

A list of some of the known terrestrial invertebrates is below. The menu at the top of this page links to a sampling of these species.

References and research papers

- Bioeconomy Science Institute: What bug is it?

- Bioeconomy Science Institute: ID keys and guides

- 2024: Invertebrate communities of the Cass, Ashley, and Aparima Rivers and methods for monitoring impacts of management and environmental change (PDF)

- 2022: Murray; Invertebrate biodiversity of the Ashley-Rakahuri and Cass Rivers: impacts of weeds and flooding

- 2021: Murray BRRI project 3387: Summary of interim report June 2021 The influence of weeds and weed management on invertebrates of the Ashley, Cass & Aparima Rivers

- 2019: Murray Invertebrate biodiversity and management on braided rivers (2019 Braided Rivers Seminar)

- 2019 (DOC): Braided River Research and Management Priorities: terrestrial invertebrates, lizards, terrestrial native plants, terrestrial weed invasions, and geomorphology, wetlands, river mouths and estuaries

- 2018: Schori et al; Evidence that reducing mammalian predators is beneficial for threatened and declining New Zealand grasshoppers New Zealand Journal of Zoology

- 2017: Gray and Harding (DOC) Braided river ecology: a literature review of physical habits and aquatic invertebrate communities Science for Conservation 279 (DOC)

- NIWA: Guides to Freshwater invertebrates

- Entomological Society of New Zealand

- See also Ecology/references