What's a 'braided' river?

Globally, braided rivers are rare. They occur only where a very specific combination of climate and geology allows rivers to form ever-changing and highly dynamic ‘braided’ channels across a wide gravelly riverbed (see ‘braidplains’).

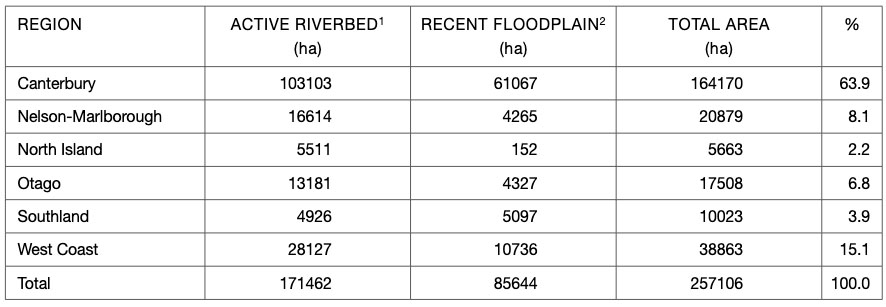

New Zealand is a braided river hot-spot. Almost 64% of our braided rivers are in Canterbury, with a catchment of over 164,170ha. Indeed, the entire Canterbury Plains was formed by sediment and gravel carried from the Southern Alps by braided rivers as they flowed to the coast. Southland, the West Coast and Otago regions also feature spectacular braided rivers such as the Makarora River, which flows from Mt Aspiring National Park into Lake Wanaka.

The extent of terrestrial braided river habitats (from: Management and research priorities p.5)

Note: data is indicative only because mapping the precise extent of braided rivers depends on the precision of base data and spatial definition of habitat types. This mapping was based on the examination of NZMG 260 topovectors (Land Information New Zealand), Wilson (2001), digitalised from air photography and expert advice.

1. ‘Active riverbed’: areas of unstable gravels and flowing channels

2. ‘Recent floodplain’: flat land either side of the active riverbed. Floodplains may be reactivated if rivers change their course or may be flooded in the highest floods.

See the page on ‘braidplains‘ for more information.

Why do rivers 'braid'?

Braided rivers both erode and deposit gravel, depending on the gradient of the river and speed and volume of the water. Flow changes according to the amount of rainfall and/or snowmelt. The volume and speed of the water is measured in cubic metres per second or cumecs. During low flow periods (low cumecs), gravel is dropped and the river ‘braids’ into smaller channels around temporary gravel islands. Following storms and snowmelt, minus the effects of abstraction of water for irrigation, the rivers rise (high cumecs) and some or all of the braids join to become a single wide channel that covers and sometimes washes away the gravel islands.

During periods of high flow, unless contained by geological features such as tall terraces and valley walls, or man-made flood defences, braided river naturally wander across the landscape. This area as known as the braidplain. Only when water levels are very high will the braidplain be inundated. When water levels drop, new channels and islands will appear in different places on the braidplain. This process, called lateral migration, and the deposit of large volumes of gravel and sediment is what formed the Canterbury Plains.

Why are they special?

Centuries of development have largely robbed the Canterbury Plains of its forest, wetland, and coastal habitats. The biologically rich braided rivers are one of the last remaining strongholds of biodiversity in the Canterbury Plains, forming a vital ecological link from the mountains to the sea. However, while braided river plants and animals evolved strategies to live in these dynamic and volatile environments, many species are declining at an alarming rate due to the activities of people. Several are at risk of extinction. The reasons for this are discussed in the section on threats and the section below.

See this 2023 presentation: Braided River Revival & Making Room for Rivers (PDF)

Creating Canterbury Plains

Around 40 million years ago, tectonic forces pushed the edges of two plates together along the Alpine Fault. This mountain building or orogeny created the Southern Alps – Kä Tiritiri o te Moana. Over millions of years, a staggering 20 kilometres-thick section of the Earth’s crust was uplifted. Most of it was eroded by heavy rain and snowfall (as much as 12 metres annually) over the mountains. Glaciers came and went, grinding through the Southern Alps, creating huge volumes of moraine gravels and sediment. With so much precipitation, fast-flowing rivers carried the gravels and sediment to the coast east of the Main Divide, depositing the material into the ocean until it built into deltas. Over time, the deltas joined into alluvial fans until they eventually created the giant ‘megafan’ that we now call the Canterbury Plains.

The process continues today, with the mountains continuing to rise around 20mm/year, about the same rate as they’re eroding, ensuring an endless supply of sediment as rainfall strips an estimated 10,000 tonnes/km2 annually from the mountains.

Losing coastal lands

“The conventional wisdom is that you harvest flood water in the winter and store it until it’s needed in the summer. However, floods are required to carry gravels to the coastal zone and if there’s not enough gravel, the waves get hungry and start eroding the land.” – Dr Scott Lanard, NIWA

Most of this sediment was once spread across coastal deltas, building the coastline outward. However, the rivers have now been confined by stop banks and levees. While this prevents them from flooding, it also stops them from wandering over the coastal lands and adding thousands of tonnes of sediment as they go. Now, instead of building up our coast, most of this gravel and sediment is carried out to sea. Except in Kaikoura where earthquakes have lifted the coastline in places, the Canterbury coastline is now eroding. Soon, long stretches of it will be inundated by rising sea levels.

The Ahururi River braidplain

The Ahuriri River. The red line is 2019 pre-High Court decision understanding of the bed of a braided river based on 1-in-50-year flood modelling (where available) and consistent with earlier caselaw. Because the RMA does not recognise the braidplain as integral to the natural variability of flow of braided rivers , the green line is the new legal definition of a braided river.

Who is responsible for managing our braided rivers?

Conflicting priorities, uncertainty over jurisdiction, and confusion over the definition of what exactly is a braided river have led to their degradation. The following is a brief outline of a contentious history that’s still unfolding.

1991: Water resources in New Zealand are managed through the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA). Under the RMA, any activity that may affect rivers requires an application for a Resource Consent outlining those activities and how any potential damage will be prevented. However, the RMA defines riverbeds much the same way they are defined elsewhere in the world, as ‘the space of land which the waters of the river cover at its fullest flow without overtopping its bank’.

But by definition, large sections of these globally rare types of rivers, ie, the riverbeds’ braidplains are dry most of the time. This has resulted in the ‘dry’ areas either side of the active channels being instead thought of as ‘land’ that could be converted to agriculture.

The problem is compounded because rivers are managed in different ways by:

- Land Information New Zealand (LINZ), responsible for managing pest plants (weeds) on Unallocated Crown-owned Lands (‘Crown’ riverbed)

- Department of Conservation (DOC), responsible for managing rivers on Conservation lands.

- Regional Councils, responsible for managing water resources (including riverbeds) through RMA.

- AMF rights; some landowners have historic property rights to the middle of the riverbed. These are known as Ad medium filium (AMF) rights.

1998: Following a drought, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Ministry for the Environment, and one of the Regional Councils, Environment Canterbury (ECan), develops the Land & Water Regional Plan.

2007: ECan conceives the Canterbury Water Management Strategy (CWMS), a collaborative stakeholder engagement strategy intended to address the growing water problems. The CWMS is adopted by Canterbury Mayoral Forum in December that year, to address water-related issues in the region through district Zone Committees, each with their own Zone Implementation Programme (ZIP).

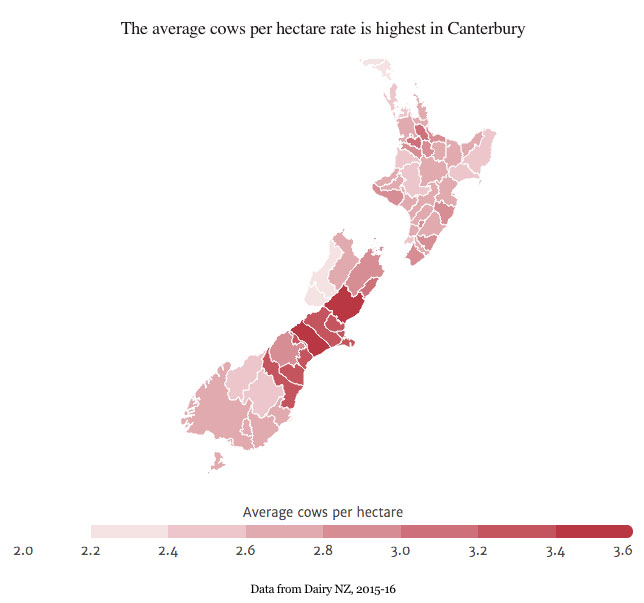

2010: March: While Canterbury farms are rapidly being converted to dairy farms courtesy of irrigation schemes, the democratically elected regional council, ECan, is sacked by then MP for the Environment Nick Smith, because it had, ‘Failed to introduce a water plan for the region, allowing it to make the most of its alpine water and reap the economic rewards of large scale irrigation.’ (Radio NZ). The Council is replaced by non-elected Commissioners. July: the Canterbury Water Management Strategy (CWMS document) is published.

2012: Land, Air, Water Aotearoa (LAWA) is established with a view to helping local communities find the balance between using natural resources and maintaining their quality and availability. Initially, a collaboration between New Zealand’s 16 regional and unitary councils, LAWA is a partnership between the councils, Cawthron Institute, Ministry for the Environment and Massey University.

2015: ECan, still led by Commissioners, releases a damning report showing that between 1990-2012, some 11,300ha of formerly forested or ‘undeveloped land’ on braidplains had been converted to intensive agricultural use.

2017: The Braided River Action Group (BRAG) is convened in response to the above report on the loss of braided river habits to agriculture. Comprising representatives from ECan, Territorial Authorities, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, DOC, LINZ, Forest & Bird, Fish & Game and Federated Farmers, the members have a range of roles, responsibilities, and interests in braided rivers. There is also a range of existing policy and regulation. The focus of the group is the seven large, alpine-fed braided rivers: Clarence/Waiau Toa, Waiau, Hurunui, Waimakariri, Rakaia, Rangitata, and Waitaki rivers); and three foothill-fed rivers: Ashley/Rakahuri, Selwyn/Waikirikiri (part), and the Ashburton/Hakatere.

2017-2018: The continued encroachment of dairy farm development into the braidplains of Canterbury’s major braided rivers seriously threatens their ecological integrity. ECan releases more reports (Braidplain Delineation Methodology and Braided Rivers: Natural characteristics, threats, and approaches to better management) to assist in defining the boundaries of braided rivers so that they can be better managed under the RMA. ECan also launches the Bridge project, to work with stakeholders to develop a common approach to managing braided rivers.

2019: The Bridge project is halted following a High Court decision in December 2018 that the RMA definition of a riverbed does not include braidplains. Environment Canterbury appealed the decision. In October the appeal was lost. Meanwhile, in September, the updated Canterbury Water Management Strategy (CWMS) is released. Given the High Court and Court of Appeals decision, there are currently no clear statutory rules that prevent the continued conversion of these globally rare ecosystems into intensive agriculture.

December: The Productivity Commission Report includes recommendations that rivers ‘be given more room to move’ (see Box 9.5 in the Report)

2020: May: Decisions on amendments to the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management is published. The 2020 set of targets for the Canterbury Water Management Strategy has added interim targets for 2025 and 2030.

October: ECan start the process of reviewing the Government’s Essential Freshwater package.

2021: January: Nine New Zealand river experts explain why we should release New Zealand’s strangled rivers to lessen the impact of future floods. May: Rivers flood. July: ECan report clearly shows that braidplains in mid-Canterbury hills are still being converted to agriculture at a staggering rate.

2022: August – Ministry for the Environment: National Adaptation Plan to address climate change paints a clear picture: rivers must be given room to move to accommodate increasing frequency of atmospheric rivers.

Waiau River & irrigated braidplain

Further information & references

- Braidplain or floodplain? What’s the difference and why does it matter?

- Resource Management Act 1991

- Canterbury Water Management Strategy

- Natural Character of Braided Rivers

- Targets and Goals (October 2020)

- Updated CWMS Strategic Framework document (September 2019)

- Land Air Water Aotearoa LAWA – easy to find data on all New Zealand rivers

- ECan document library: enter the river or catchment name in the ‘keywords‘ search field

- DOC catalogue of scientific publications: enter the relevant search terms in the ‘search’ dialogue box. You may need to vary your search, for example ‘black stilt’ gives far more results than ‘kaki’ or ‘kakī’

- Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) Biosecurity Control Programme (weed clearing, rabbit and wallaby culling)

- 2021: Greenep and Parker; Land use change on the margins of lowland Canterbury braided rivers, 2012-2019 (ECan report)

- 2021: Grove & Greenep; Land use change of braided river margins (presentation on the above to the Braided Rivers Seminar July 2021)

- 2021: Grove et al; Agricultural land use change in mid-Canterbury hill and high country, 1990- 2019: implications for indigenous biodiversity and ecosystem health (ECan report)

- 2021: Gray; Braided river ecosystems: physical habitat, ecological complexity and the management conundrum (presentation on the above to the Braided Rivers Seminar July 2021)

- 2021: Griffiths, Surman & Owen; Braided River Revival Whakahaumanu ngā awa ā pākahi and steering the river management ship, (Braided Rivers Seminar July 2021)

- 2021: Hoyle; Effects of flood harvesting on fine sediment deposition in braided rivers (Braided Rivers Seminar July 2021)

- 2021: Lanard; The Future Shape of Water, Water And Atmosphere, NIWA

- 2021: Davey; The plight of the foothills-fed Canterbury braided rivers (Braided Rivers Seminar July 2021)

- 2019: Productivity Commission: Local government funding and financing (financing and management of rivers given the climate change risks)

- 2019: Joy & Talbot-Jones (eds.); A Potted History of Freshwater Management in New Zealand, Policy Quarterly, Victoria Wellington University Vol 15:3 August 2019

- 2019: (NIWA); New Zealand Fluvial and Pluvial Flood Exposure, National Science Challenges/Deep South Challenge (see also: Deep South Challenge webpage)

- 2019: (ECan) Pompei, Grove & Cuff; Monitoring extent of available habitat for indigenous braided river birds in Canterbury – a 2012 Baseline

- 2019: DOC; Management and Research Priorities: terrestrial invertebrates, lizards, terrestrial native plants, terrestrial weed invasions, and geomorphology, wetlands, river mouths and estuaries

- 2019: (BRaid); Blog post ‘In Defence of Braided Rivers as ‘public goods’

- 2019: (Braid); Blogpost ‘Defining a ‘braided’ river’

- 2018: ECan; High country spring-fed streams: effects of adjacent land use

- 2018: ECan; documents accompanying the Bridge Project

- 2018: BRaid; Blog post outlining the rational of the Bridge Project

- 2018: ECan; Braided Rivers; natural characteristics, threats and approaches to more effective management

- 2018: NIWA; Braidplain Delineation Methodology

- 2017: (ECan) Keeling & Grove; Addressing Land Use Change in Braided Rivers (BRaid seminar)

- 2017: NIWA; Modelling vegetation-impacted morphodynamics in braided rivers

- 2017: Hughey; Keynote address: Local, regional, national and international aspects of braided river management (BRaid seminar)

- 2017: (DOC) Maloney; Opportunities and priorities for future braided river conservation (BRaid seminar)

- 2017: (DOC) O’Donnell; Values and management of lowland braided rivers for birds (BRaid seminar)

- 2016: BRaid; Teaching resources (PDF) or (iPad)

- 2016: Forest & Bird; Important Bird Areas on Braided Rivers – links to list of 3-7 page PDF files, by river name. These were extracted from Forest & Bird’s 177-page 20Mb file on all rivers, lakes, and coastal areas.

- 2016: DOC; Management and Research Priorities for New Zealand Braided Rivers

- 2015: ECan; Land Use Change on the Margins of Lowland Canterbury Braided Rivers 1990-2012

- 2015: Radio NZ; Democracy and Water Rights

- 2014: Science Blogs NZ; Using models to understand and protect our braided rivers

- 2014: NIWA; Modelling channel dynamics in braided rivers

- 2012: Salmon; Canterbury Water Management Strategy–a case study in collaborative governance. Ecologic report prepared for the Ministry of the Environment.

- 2011: Whitelaw; The Vulnerability of Tuhaitara Coastal Park to Rising Sea-levels

- Hearnshaw et al (undated): Ecosystem Services Review of Water Storage Projects in Canterbury: The Opihi River Case

- 2007: DOC; Braided River Ecology: a literature review of physical habitats and aquatic invertebrate communities