Chicks on a Farm

Most of the world’s gull species are associated with marine coastal environments. Not so NZ’s black-billed gull. This endemic species is an inland specialist, which usually breeds on our braided rivers, particularly in eastern and southern parts of the country. Its numbers have plummeted over the last decades, to the extent that it is now said to be the world’s most threatened gull species.

Black-billed gulls used to nest in their thousands on the Ashley-Rakahuri River, but colonies have only been located occasionally in recent years, with none present for the last two seasons. So, it is a welcomed event to have a local one this year, made even more interesting by the fact that they have chosen to establish themselves in the middle of an actively managed dairy farm about 300m from the river. This is unusual, as although they can often be seen feeding in irrigated paddocks, and have been known to nest on farmland, this is the first record of a colony on improved pasture regularly grazed by cows. Not only that, but a centre pivot spraying water regularly passes over them.

The birds were first attracted by cultivation bringing grubs and insects to the ground surface, and in early November chose to start building nests where grass had been recently sown. Numbers soon grew to around 600 birds with 250 nests in a tightly packed colony. When non-breeding birds are added, the total number present can be close to 800. Chicks started hatching in early December.

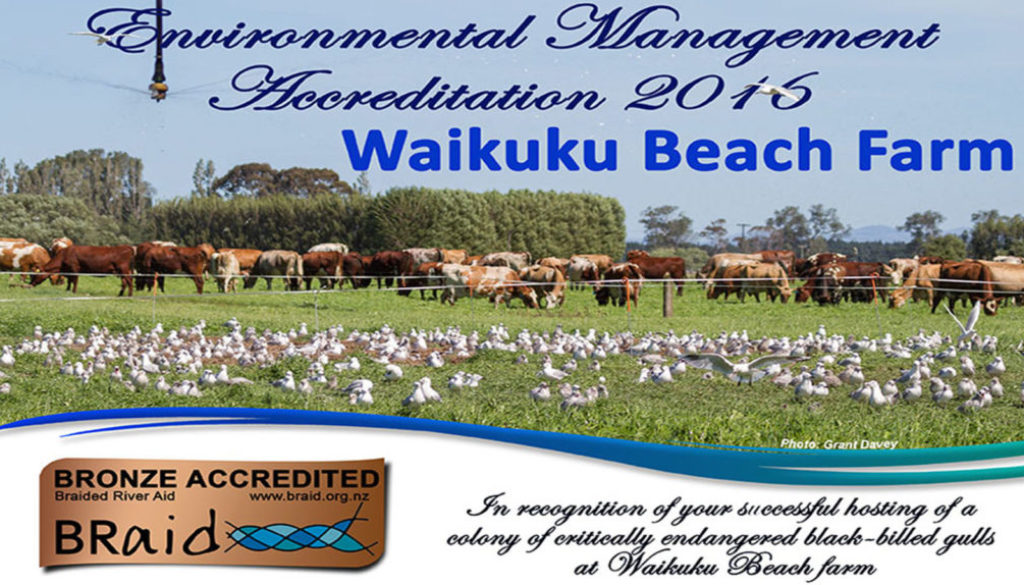

Although farm owner, Tim Delaney, and manager, James Henderson, were initially intrigued by the birds’ arrival, they did wonder how it might interfere with everyday farm management, such as irrigation, grazing and moving cows. At this time, members of the local Ashley-Rakahuri Rivercare Group were alerted to the bird’s presence and visited the site. Discussions were held as to how best to maximise the chances of breeding success while minimising disturbance to normal farm management disturbance. Tim and James were keen to assist in obtaining a win-win outcome.

A single hot tape has been run around the colony so that stock can graze the paddock as normal. Apart from the eaten-down grass, the only evidence of their presence is a slightly worn path around the colony margin where cows have stood to gaze at their new neighbours. As the chicks grow older, they group up into a single large mob or crèche, which can be quite mobile. Extra attention may be needed to ensure that they do not wander into harm’s way, but such a risk will not last long, as they should be fledged and flying by the New Year.

Needless to say, ornithologists are following this unusual situation closely. They are aware that the major threats to breeding birds on riverbeds are floods, human disturbance, woody weed invasion and predators. The first three are not an issue on a dairy farm, and predator numbers are likely to be lower than ‘in the wild’. All the same, traps have been set along adjacent fence lines. These have been supplied by BRaid (braided river aid), an umbrella group which has a partnership project specifically aimed at getting landowners and the public to participate in braided river bird conservation actions such as this.

On a recent visit, the flight line of parent birds arriving to feed chicks was followed. It led a short distance to a nearby paddock, where stock were grazing. In amongst the quiet, cud-chewing Jersey cows were numerous gulls moving around gathering food. So it seems that the dairy farm not only hosts a thriving gull colony, but also a ready food source. There are obviously aspects of modern farming which can work in well with indigenous conservation. All it takes is better recognition of the compatible factors, and then working together to make the most of them.